Why NBME Pattern Recognition Is the Core Skill of Step 1

Step 1 is best understood as a pattern-recognition exam disguised as a basic science test. While foundational knowledge is necessary, it is not sufficient. The National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) does not reward exhaustive reasoning or encyclopedic recall; it rewards rapid identification of familiar clinical and mechanistic patterns embedded within deliberately noisy question stems.

High-scoring examinees are not solving novel problems from first principles on test day. They are matching each vignette to a limited library of well-learned templates: classic disease presentations, canonical biochemical failures, predictable pharmacologic adverse effects, and recurrent physiologic mechanisms. Once the correct template is activated, most answer choices can be eliminated almost reflexively.

This is not shortcutting or “gaming the exam.” It reflects how clinical reasoning actually works. Expert physicians do not re-derive diagnoses each time they see a patient; they recognize patterns shaped by repeated exposure. Step 1 tests whether you have begun to think this way.

Importantly, the NBME designs questions assuming that many test-takers will overprocess. Long stems, extraneous labs, and partial symptom overlap are intentional. These elements are included not because they are essential, but because they punish inefficient readers and reward disciplined pattern recognition.

The central thesis of this article is simple: if you can reliably identify the NBME’s intended pattern within the first 20–30 seconds of a stem, you will answer faster, eliminate distractors more confidently, and preserve cognitive bandwidth for truly difficult questions.

The Anatomy of an NBME Stem: Isolating the Diagnostic Core

Every NBME-style question contains far more information than is required to answer it. Your first task is to extract the diagnostic core—the minimal set of clues that uniquely identifies the tested concept.

In most Step 1 questions, the diagnostic core consists of no more than three elements:

- Who: Age, sex, pregnancy status, or genetic background

- When: Time course (acute, subacute, chronic, episodic)

- What: One defining symptom, lab abnormality, or physiologic failure

For example, “young child + hypoglycemia + hepatomegaly” should immediately activate a glycogen storage disease framework. “Elderly smoker + painless hematuria” should narrow to a urothelial malignancy pattern before you even finish reading the stem.

Everything else—the normal electrolytes, the mildly abnormal vitals, the unrelated family history—is usually contextual noise. NBME writers include this information specifically to test whether you can distinguish signal from distraction.

A useful heuristic: if removing a detail does not change your leading diagnosis, it was not part of the diagnostic core. Training yourself to consciously identify and name the core after each practice question dramatically accelerates pattern acquisition.

The Finite Set of NBME Pattern Archetypes

Although Step 1 feels vast, the NBME repeatedly tests a relatively small number of pattern archetypes. Recognizing which archetype a question belongs to immediately constrains the solution space.

| Archetype | Stem Clues | Primary Skill Tested |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism failure | Pathway disruption, enzyme loss | Biochemistry/physiology linkage |

| Classic presentation | Textbook symptom cluster | Diagnosis recognition |

| Drug toxicity | Medication exposure + new symptom | Pharmacology adverse effects |

| Complication pattern | Known disease + downstream problem | Disease progression |

| Risk-factor association | Demographics + exposure | Epidemiologic reasoning |

Once you classify a question into one of these archetypes, you should mentally generate a short list of candidates that fit. If the stem does not clearly belong to a mechanism question, do not waste time calculating pathways. If it is a drug question, the answer is almost never a disease entity.

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

- Adaptive QBank with rationales that teach

- CCS cases with live vitals & scoring

- Progress dashboard with readiness signals

Systematic Distractor Elimination: Why Wrong Answers Are Wrong

NBME distractors are deliberately engineered to be tempting. They are not random incorrect options; each one is designed to exploit a specific reasoning error—anchoring, premature closure, or incomplete pattern recognition. Your job is not to debate which option is “most right,” but to identify which options are structurally incompatible with the stem’s dominant pattern.

High-yield elimination rules (fast screen)

- Temporal inconsistency: timeline doesn’t fit (acute vs chronic, episodic vs progressive)

- Population mismatch: age/sex/exposure makes option unlikely

- Mechanistic mismatch: option requires a pathway not suggested by the stem

- Severity mismatch: magnitude of findings doesn’t justify the diagnosis/mechanism

- Localization mismatch: neuroanatomy/physiology doesn’t map to the deficits

- “Two-step” mismatch: option is downstream, but stem asks upstream (or vice versa)

One-contradiction rule

You do not need a full explanation to eliminate. One clear contradiction between stem and option is enough. This prevents the classic Step 1 spiral: “But it could also be…”

Distractor Taxonomy (what the NBME is doing)

| Distractor Type | How It Tempts You | Fast Elimination Check | Common Step 1 Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-clue lookalike | Shares one buzzword (e.g., “diarrhea,” “ring-enhancing,” “eosinophils”) | Ask: does it explain the whole stem (time course + key labs + risk factor)? | ID, GI, heme/onc |

| Time-course trap | Correct concept, wrong timeline | Acute vs chronic vs episodic—does the mechanism match speed? | Cardio, neuro, endocrine |

| Age/sex/exposure mismatch | Classic diagnosis in the wrong population | Would this be “first presentation” in this demographic? | Peds genetics, OB, geriatrics |

| Upstream vs downstream swap | Confuses cause with consequence | Identify what the question asks: initial defect vs compensatory response | Renal phys, acid-base, endocrine |

| Similar phenotype, different mechanism | Same symptom cluster, different pathophysiology | Pick the mechanism that best fits the discriminating clue (lab, trigger, reflex) | Neuro, pharm, immuno |

| True statement, wrong question | Answer is factually correct but not what’s being asked | Restate the task verb: “most likely cause” vs “best next step” vs “MOA” | All domains |

| Vague-sounding generality | Feels “safe” when unsure | Eliminate if non-specific and other options are mechanistic | Biostats, micro, path |

Annotated NBME-style sample stem (distractor elimination in action)

Stem: A 24-year-old woman has episodic headaches, palpitations, and sweating. BP is 190/110 mm Hg during episodes. Between episodes she feels well. Urinary catecholamine metabolites are elevated.

Question: The underlying mechanism most likely involves increased activity of which enzyme?

Diagnostic core: episodic sympathetic surges + high BP + catecholamine metabolites → catecholamine-secreting tumor pattern

Category: mechanism/biochem (enzyme)

Distractor elimination:

- Temporal mismatch: chronic endocrine HTN etiologies that are not episodic drop out fast

- Mechanistic mismatch: enzymes unrelated to catecholamine synthesis are eliminated immediately

- Upstream/downstream: if asked “enzyme,” pick synthesis pathway (e.g., tyrosine hydroxylase), not a receptor effect

Takeaway: Once you identify “episodic catecholamine surge,” most options die on mismatch rules before you “know everything” about pheochromocytoma.

Using Answer Choices to Reverse-Engineer the Question

Reading the answer choices before the stem can accelerate pattern recognition because it reveals the NBME’s intent. Your goal is to identify the “answer-choice category” (enzymes, cytokines, diagnoses, drugs, organisms, graphs) and then read the stem as a targeted search for confirmation and disconfirmation.

Answer-choice category cues

- All enzymes/intermediates → metabolic pathway defect

- All cytokines/receptors → immunology signaling/hypersensitivity

- All diagnoses → classic presentation recognition

- All drugs → pharmacology MOA/adverse effect

- All organisms → micro identification (risk factor + morphology)

- All graphs/curves → physiology or biostats interpretation

Active reading script

- “What domain are they testing?”

- “What 2–3 discriminators separate these options?”

- Scan stem only for those discriminators.

Annotated NBME-style sample stem (reverse-engineering)

Answer choices (seen first): IL-4, IFN-γ, IL-17, TGF-β, IL-2

What this tells you: This is an immunology T-helper/cytokine differentiation question.

Stem: A patient with asthma has increased mucus production and eosinophilia. Biopsy shows airway smooth muscle hypertrophy. Which cytokine is most associated with this response?

Discriminators to look for:

- Eosinophils + allergy → Th2 pattern

- Asthma + IgE class switching → IL-4/IL-13 family

- Neutrophilic inflammation → think Th17 (not present here)

Takeaway: You didn’t need to “read for comprehension.” You needed to confirm Th2, then pick the Th2 cytokine from the list.

NBME Cognitive Traps That Break Pattern Recognition

The NBME repeatedly tests not just knowledge, but your vulnerability to predictable cognitive errors. These traps are consistent across forms and years. If you can name the trap while reading, you regain control of the question.

Anchoring

One loud clue hijacks your diagnosis (e.g., one lab abnormality). The fix: force yourself to explain the whole stem, not one data point.

Hybrid stems

Two patterns are mixed. The fix: pick the diagnosis that explains the majority with the fewest assumptions (parsimony).

True-but-irrelevant

Extra correct facts appear. The fix: restate the task verb (“most likely cause,” “MOA,” “next step”).

Annotated NBME-style sample stem (trap recognition)

Stem: A 67-year-old man presents with weight loss and cough. Chest imaging shows a central lung mass. Serum sodium is 122 mEq/L. He is euvolemic on exam.

Trap: Anchoring on “hyponatremia” alone can make you chase renal/GI causes.

How to beat it (in 10 seconds):

- Central lung mass + euvolemic hyponatremia → SIADH pattern

- Then ask: which tumor is classically central and linked to SIADH? (small cell)

- Ignore other hyponatremia etiologies—population + context dominate

Takeaway: The “loud clue” (Na 122) is real, but it is meant to pull you away from the cancer pattern. Context wins.

Deliberate Training of Pattern Recognition During Dedicated

Pattern recognition is trained the same way clinical expertise is trained: repeated exposure, immediate feedback, and structured reflection. Passive review builds familiarity, but only question-stem repetition builds speed. Your dedicated period should be engineered to convert knowledge into templates you can deploy instantly.

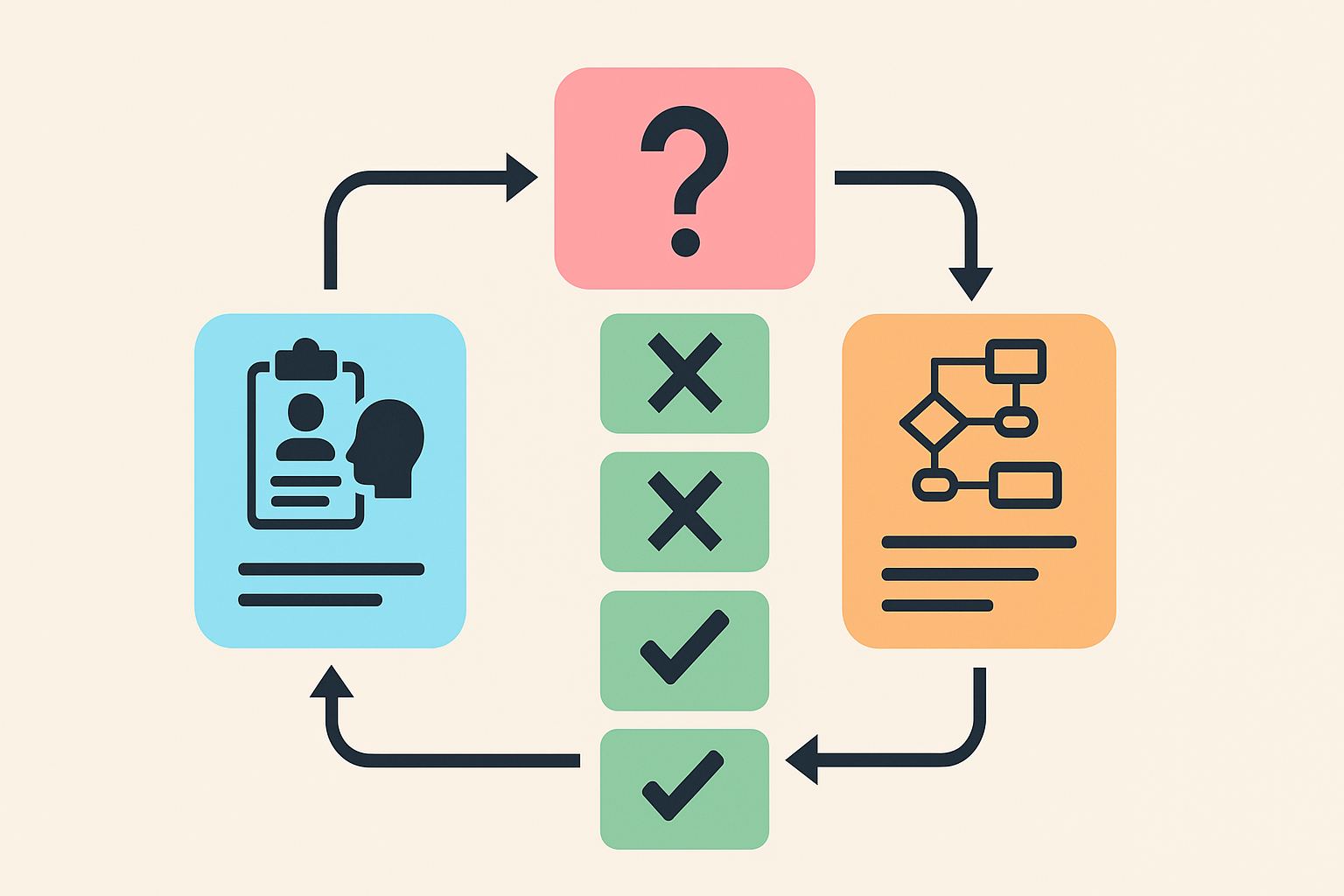

The 3-step “Pattern Loop” after every question

- Name the pattern: “drug toxicity,” “enzyme deficiency,” “complication,” “localization,” etc.

- Extract the discriminators: the 2–3 clues that made it that pattern

- Write the anti-pattern: what would have made a common distractor correct?

Make your review searchable

Don’t tag misses as “renal” or “cardio” only. Tag them as:

- time-course error

- population mismatch

- mechanism vs downstream confusion

- anchoring / overthinking

If you want a structured framework to organize this (and avoid random review), the MDSteps 9-page Complete Bucket System PDF is designed to help you classify every question into repeatable buckets and turn misses into pattern templates.

MDSteps supports this workflow by tagging questions by underlying mechanism and presentation, auto-generating flashcards from missed stems, and providing analytics that highlight recurring reasoning errors rather than superficial content gaps—so you spend your time fixing the specific pattern failures that will repeat on test day.

Annotated NBME-style sample stem (training the pattern loop)

Stem: A newborn develops vomiting, lethargy, and seizures after feeding. Labs show hyperammonemia. No evidence of liver failure. Which enzyme deficiency is most likely?

Pattern Loop example:

- Name the pattern: newborn + feeding-triggered neuro symptoms + hyperammonemia → urea cycle defect pattern

- Discriminators: early onset, post-feeding, ammonia high, no liver failure

- Anti-pattern: if hypoglycemia + hepatomegaly dominated, think glycogen storage; if ketoacidosis, think organic acidemia

Takeaway: The “anti-pattern” step is what prevents you from falling for next time’s distractor variant.

References

- NBME. USMLE Step 1 Content Outline.

- Norman G. Research in clinical reasoning: past history and current trends. Medical Education.

- Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and expert performance. Psychological Review.